By Jo White and Suzanne Rogers

Only a few months ago the term ‘social distancing’ wouldn’t have meant much to most of us but now the term is familiar to the vast majority of people. The coronavirus pandemic is an unprecedented threat causing significant disruption of lives and it is happening on a global scale. Messaging surrounding how to keep safe and protect others has caused a spectrum of behavioural responses; some people practised isolation before it was advised by the government and some have disobeyed restrictions placed by governments both regarding social distancing and face masks. This blog explores why there has not been full compliance with the advice.

Social behaviour as a habit

We have evolved to be social – we live in groups, we gain emotional comfort and stimulation from social connection, including physical connection, and social behaviour is cemented in our rituals and habitual behaviours.

As much as 45% of our daily behaviour is habitual, we do it without thinking. Habits are hard to break and most of us can relate to the fact that habits are stronger than intention. The seeming reluctance of some to practice social distancing might be partly due to people acting automatically in ways that go against the social distancing recommendations rather than intending to do so.

Related to habitual behaviour is our tendency to enact familiar patterns of behaviour. Even if we were intending to practice social distancing, when faced with the very common experience of visiting a shop to purchase groceries, our habitual behaviours (e.g. the distance we leave between ourselves and the person in front of us in the queue or when waiting to look at the same product) might be enacted before we even realise what we are doing!

Coping mechanisms distort risk assessment

We are notoriously bad at measuring risk. Cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias, come into play: we are more likely to take on information if it fits with what we already believe to be true than if it goes against our current beliefs and understanding of a situation. The pandemic is unprecedented, none of us have lived through anything similar, so we seek information that fits with what we do know and can draw on from our previous experiences. For some people this means that reports that down-play the risk (e.g. “It’s only flu”) might have more traction when assessing risk than reports that highlight the virulence and true risks involved.

There is a social element here too – we tend to look to others to confirm that what we are doing is acceptable. If we see other people not leaving a two metre gap between themselves and the next person in a queue, in the park or on the beach, we deem that to be acceptable behaviour, especially if they are people who influence us or seem to be like us. Some people might feel embarrassed about behaving differently to the ‘norm’ if many people around them are not keeping their distance or wearing a mask, perhaps not wanting to be perceived as being over-zealous.

As mentioned above, some people cope by minimising the risks through their internal dialogue. The initial reporting about the virus fuelled this perception as phrases such as ‘it’s only flu’, ‘it only affects older people with pre-existing issues’ and so on were frequently used. A powerful meme on Facebook states that if you knew that three out of 100 sweets were poisonous and could kill you, most people would not take the risk of eating any of the sweets. However, in the face of the pandemic some people have dismissed a similar chance of being seriously affected by the disease.

Other barriers to keeping our distance

In the UK we are very privileged to have freedom of speech and expression. As such, some people have a sense of entitlement to do what they want. It is not at all usual for the government to place restrictions on behaviour and although for some this serves to highlight the importance of complying with the unprecedented measures, others perceive it as a threat to their rights. The human tendency to create conspiracy theories has also shown itself to be relevant with regards to this disease.

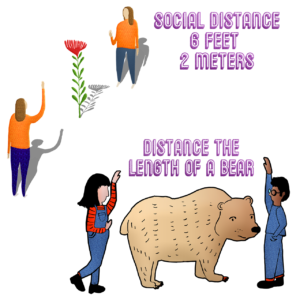

Another barrier to enacting social distancing might be that some people do not understand what two metres looks like. Initial messaging focused on slogans such as “Two metres distance determines our existence” but quickly moved to include ways to help people to visualise two metres, for example asking people to imagine someone lying on the floor between themselves and the next person, or that two metres is approximately the length of two shopping trolleys. Interest groups have created messaging to explain it in terms that resonate with them, for example a horse is about six feet long so encourage animal lovers to imagine a horse between two people. Providing cues in the environment to facilitate social distancing behaviour such as tape and stickers on the floor have also been widely introduced, highlighting how sometimes visual and contextual cues can facilitate behaviours without having to include messaging as such.

Sadly, there are very concerning and upsetting effects of the restrictions that also form barriers to social distancing. Obeying social distancing by keeping away from others will put many vulnerable people at increased risk – for example those experiencing domestic violence, and abject poverty will be forced into closer proximity with abusers and decrease opportunity for earning money respectively.

How can we apply behaviour science to the social distancing rules to increase compliance?

Effective messaging is vital to encourage compliance with social distancing rules, especially as some form of social distancing is likely to be needed for some time. Messaging should:

- appeal to people’s values and what they care about

- use positive language to encourage compliance where possible

- celebrate those who are compliant to encourage a feeling of solidarity

- feature influential people to encourage behaviour change through role modelling

- nurture a sense of duty – encourage people to do their bit for the fight against the pandemic

- demonstrate the benefits – e.g. show that the rates of transmission are greatly affected by the number of people each of us comes into contact with

- suggest alternatives – e.g. help people to use technology to keep in touch and order provisions and perhaps even earn money

- try to mitigate for apathetic responses by creating an understanding that not keeping distance is socially unacceptable

- include cues and triggers in the environment (e.g. a two metre slogan on tape in supermarkets).

Shops and suppliers have rapidly expanded their capacities for the delivery and direct distribution of food to reduce the need for people having to come into contact with others. They have also introduced ‘one in one out’ approaches to shopping, limiting multi-customer contact with people and goods. Some smaller shops do not let people touch products that they are not intending to buy to limit spread through surface contact. Some popular beaches are restricting numbers by making the car parks bookable only in advance, changing the way we plan our activities and some parks have makers for picnic spots.

As some level of restrictions continue, we are unlikely to see a return to the typical numbers of people in shops as before the pandemic, our food acquisition habits are likely to have changed for the next few months at least if not forever. By coming together in support of the key workers that we all rely on, and together in solving challenges that cut across all levels of society, perhaps counter-intuitively, we might find that physical distancing ultimately results in drawing us closer to each other.